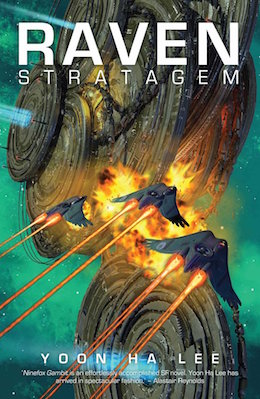

Captain Kel Cheris is possessed by a long-dead traitor general. Together they must face the rivalries of the hexarchate and a potentially devastating invasion.

When the hexarchate’s gifted young captain Kel Cheris summoned the ghost of the long-dead General Shuos Jedao to help her put down a rebellion, she didn’t reckon on his breaking free of centuries of imprisonment – and possessing her.

Even worse, the enemy Hafn are invading, and Jedao takes over General Kel Khiruev’s fleet, which was tasked with stopping them. Only one of Khiruev’s subordinates, Lieutenant Colonel Kel Brezan, seems to be able to resist the influence of the brilliant but psychotic Jedao.

Jedao claims to be interested in defending the hexarchate, but can Khiruev or Brezan trust him? For that matter, will the hexarchate’s masters wipe out the entire fleet to destroy the rogue general?

Yoon Ha Lee’s Raven Stratagem—the sequel to Ninefox Gambit—is available June 13th from Solaris.

Chapter Two

When Neshte Khiruev was eleven years old (high calendar), one of her mothers killed her father.

Until then, it had been an excellent day. Khiruev had figured out how to catch bees with your fingers. You could crush them, too, but that wasn’t the point. The trick was to ease up behind them and apply polite, firm pressure to trap them between your thumb and forefinger. They rarely took offense as long as you released them gently. She wanted to tell her mothers about the trick. Her father wouldn’t have been interested; he couldn’t stand bugs.

Khiruev came home earlier than usual to show them. When she stepped inside, she heard Mother Ekesra and her father arguing in the common room. Mother Allu, who hated shouting when she wasn’t the one doing it, was hunched in her favorite chair with her face averted.

Her father, Kthero, was a teacher, and Mother Allu worked with the ecoscrubber maintenance team. But Mother Ekesra was Vidona Ekesra, and she reprogrammed heretics. The Vidona faction had to educate heretics to comply with the hexarchate’s calendrical norms so that everyone could rely on the corresponding exotic technologies.

Mother Allu spoke first, without looking at her. “Go to your room, Khiruev.” Her voice was muffled. “You’re an inventive child. I’m sure you can entertain yourself until bedtime. I’ll send a servitor with dinner.”

This alarmed Khiruev. Mother Allu often went on about the importance of eating together instead of, for instance, straggling in late because you’d been taking apart an old game controller. But this looked like a bad time to needle her about it, so she obediently traipsed toward her room.

“No,” Mother Ekesra said when she was almost to the hallway. “She deserves to know that her father’s a heretic.”

Khiruev stopped so suddenly that she almost tripped over the floor. You didn’t joke about heresy. Everyone knew that. Was Mother Ekesra being funny? It wasn’t true what they said that the Vidona had no sense of humor, but an accusation of heresy—

“Leave the child out of this,” Khiruev’s father said. He had a quiet voice, but people tended to listen when he spoke.

Mother Ekesra wasn’t in a listening mood. “If you didn’t want her involved,” she said in that Inescapable Logic tone that Khiruev especially dreaded, “you shouldn’t have taken up with calendrical deviants or ‘reenactors’ or whatever they call themselves. What were you thinking?”

“At least I was thinking,” Khiruev’s father replied, “unlike certain members of the household.”

Khiruev edged toward the hallway in spite of herself. This argument wasn’t going to end well. She should have stayed outside.

“Don’t you start,” Mother Ekesra said. She yanked Khiruev’s arm around until she faced her father. “Look at her, Kthero.” Her voice was flat, deadly. “Our daughter. You’ve exposed her to heresy, it’s a contamination, don’t you pay attention to the monthly Doctrine briefings at all?”

“Quit dragging this out, Ekesra,” Khiruev’s father said. “If you’re going to hand me over to the authorities, just get it over with.”

“I can do better than that,” Mother Ekesra said.

Khiruev missed what she said next because Khiruev finally noticed that, despite Mother Ekesra’s mechanical voice, tears were trickling down her cheeks. This embarrassed Khiruev, although she couldn’t say why.

“—summary judgment,” Mother Ekesra was saying. Whatever that meant.

Mother Allu raised her head, but didn’t speak. All she did was scrub at her eyes.

“Have mercy on the child,” Khiruev’s father said at last. “She’s only eleven.”

Mother Ekesra’s eyes blazed with such loathing that Khiruev wanted to shrivel up and roll under a chair. “Then she’s old enough to learn that heresy is a real threat with real consequences,” she said. “Don’t make any more mistakes, Kthero. I’ll never forgive you.”

“A bit late for that, I should say.” Kthero’s face was set. “She won’t forget this, you know.”

“That’s the point,” Mother Ekesra said, still in that deadly voice. “It was too late for me to save you when you got it into your head to research deprecated calendricals. But it’s not too late to stop Khiruev from ending up like you.”

I don’t want to be saved, I want everyone to stop fighting, Khiruev thought, but she wouldn’t have dreamed of contradicting her.

Khiruev’s father didn’t flinch when Mother Ekesra laid a hand on each of his shoulders. At first nothing happened. Khiruev dared to hope a reconciliation might be possible after all.

Then they heard the gears.

Maddeningly, the sound came from everywhere and nowhere, clanking and clattering out of step with itself, rhythms abandoned mid-stride, unnerving crystalline chimes that decayed into static. As the clamor grew louder, Khiruev’s father wavered. His outline turned the color of tarnished silver, and his flesh flattened to a translucent sheet through which disordered diagrams and untidy numbers could be seen, bones and blood vessels reduced to dry traceries. Vidona deathtouch.

Mother Ekesra let go. The corpse-paper remnant of her husband drifted to the floor with a horrible crackling noise. But she wasn’t done; she believed in neatness. She knelt to pick up the sheet and began folding it. Paper-folding was an art specific to the Vidona. It was also one of the few arts that the Andan faction, who otherwise prided themselves on their dominance of the hexarchate’s culture, disdained.

When Mother Ekesra was done folding the two entangled swans—remarkable work, worthy of admiration if you didn’t realize who it had once been—she put the horrible thing down, went into Mother Allu’s arms, and began to cry in earnest.

Khiruev stood there for the better part of an hour, trying not to look at the swans out of the corner of her eye and failing. Her hands felt clammy. She would rather have hidden in her room, but that couldn’t be the right thing to do. So she stayed.

During those terrible minutes (seventy-eight of them; she kept track), Khiruev promised she wouldn’t ever make either of her mothers cry like that. All the same, she couldn’t stand the thought of joining the Vidona, even to prove her loyalty to the hexarchate. For years her dreams were filled with folded paper shapes that crumpled into the wet, massy shapes of people’s hearts, or flayed themselves of folds until nothing remained but a string-tangle of forbidden numbers.

Instead, Khiruev ran toward the Kel, where there would always be someone to tell her what to do and what was right. Unfortunately, she had a significant aptitude for the military and the ability to interpret orders creatively when creativity was called for. She hadn’t accounted for what she’d do if promoted too high.

As it turned out, 341 years of seniority rendered the matter moot.

* * *

Khiruev was in her quarters, leaning against the wall and trying to concentrate on her boxes of gadgets. Her vision swam in and out of focus. All the blacks had shifted gray, and colors were desaturated. With her luck, her hearing would go next. She felt feverish, as though someone was using her bones for fuel. None of this came as a surprise, but it was still a rotten inconvenience.

After quizzing everyone about the cindermoth, the swarm, and the swarm’s original assignment, and making Khiruev relay his latest orders to the swarm, Jedao had retired to quarters. This had occasioned a certain amount of shuffling, since Jedao was now the ranking officer. Khiruev didn’t mind. The servitors had done their usual excellent job on short notice. But Commander Janaia, who liked her luxuries and hated disruptions, had looked quietly annoyed.

Five hours and sixty-one minutes remained until high table. Jedao had scheduled a staff meeting directly after that. Khiruev had that time in which to devise a way to assassinate her general without resorting to the Vrae Tala clause. Vrae Tala was more certain, but she thought she could get the job done without it. She wasn’t eager to commit suicide.

If she hadn’t been a Kel, Khiruev would have taken the direct route and shot Jedao in the back. But then, if she hadn’t been a Kel, Jedao wouldn’t have been able to take over so easily. Presumably Kel Command had no idea that Jedao was walking around in Captain Cheris’s body, or they would have issued a warning in response to Khiruev’s earlier inquiries.

As it was, it would be difficult to get into position to shoot Jedao without formation instinct asserting itself. Contemplating the assassination was already agonizing, and Jedao wasn’t anywhere in sight. And Khiruev was a general, nearest in rank. She was the only one with a chance of resisting formation instinct. The effect would strengthen with more exposure. If she was going to pull this off, she had to make her attempt soon.

Khiruev had always liked tinkering with machines, a pastime her parents had tolerated rather than encouraged. When on leave, she poked around disreputable little shops in search of devices that didn’t work anymore so she could rehabilitate them. Some of her projects came together better than others, and furthermore she was never sure what to do with the ones she did succeed in fixing. Currently her collection contained a frightening number of items in various stages of disassembly. Janaia had remarked that the servitors scared baby servitors by telling them that this was where they’d end up if they misbehaved.

The important point was that she had access to components without having to put in a request to Engineering. She had considered doing so anyway, since dubious military equipment was two steps up from dubious equipment she had bought from shopkeepers who beamed when paid for shiny pieces of junk. Still, she couldn’t risk arousing the suspicions of some soldier in Engineering who would report her to Jedao.

Khiruev nerved herself up, wishing she didn’t feel so dreadful, then gathered the components she needed. Small was good; small was best. It took her an unconscionably long time to lay everything out on the workbench because she kept dropping things. Once a nine-coil rolled away behind the desk and it took her three tries to retrieve it, convinced all the while she was going to break it even though it was made of a perfectly sturdy alloy.

The tools were worse. She could halfway convince her traitorous brain that she was only rearranging her bagatelles. Self-deception about the tools was harder.

She had to finish this before high table, and to make matters worse, she also had to allow for recovery time. She wasn’t confident that Jedao wouldn’t see through her anyway. But the alternative was doing nothing. She owed her swarm better than that. If only Brezan had—but that opportunity had passed.

Khiruev reminded herself that if she had survived that biological attack during the Hjong Mu campaign, the one where she’d hallucinated that worms were chewing their way out of her eyes, a minor physical reaction shouldn’t slow her down. The physical effects weren’t even the issue. It was the recurrent stabbing knowledge that she was betraying a superior.

Her palm hurt. Khiruev discovered that she had been jabbing herself with a screwdriver and stopped. Briefly, she considered removing her weapons so that formation instinct didn’t compel her to commit suicide rather than put her plan in motion, but that wouldn’t work. It would raise suspicions at high table. Her glove had a small tear in it, which knit itself back together as she watched.

The best way to proceed, it turned out, was to break down the task of assembly into the smallest imaginable subtasks so that she didn’t have to think about the end product. (She tried not to think about who she’d learned that from.) She had to scratch out some of the intermediate computations for the correct numerical resonances on a corner of her workbench, an endeavor complicated by the bench’s tendency to heal itself after a few moments. At least it got rid of the immediate evidence. It wasn’t hard to read the marks out of the material’s memory, she could do it herself with the right kind of scanner, but you had to know to do it in the first place.

Khiruev’s chest hurt, and she paused. Her hand ached from how tightly she was gripping the screwdriver. She brought it up so the blade pointed at her lower eyelid. It wouldn’t take much force to drive it into her eye.

She was a traitor no matter what she did. There was no way to be loyal both to Kel Command and to her general. She angled the screwdriver so it—

I have to kill him, Khiruev thought desperately. She couldn’t leave the swarm in the madman’s hands, not when it was needed to defend the hexarchate against the Hafn. Khiruev forced herself to lower the screwdriver. Then she dropped it with a clatter and put her head in her hands, breathing hard. She had to complete the assassination drone no matter what.

Excerpted from Raven Stratagem, copyright © 2017 by Yoon Ha Lee.